John Hughes' Love & Fury by John Conomos |

|

Television documentary, 2013; duration: 28 minutes; narration: Ramona Koval.

The

film essay, and now more recently, the video essay, have virtually become

axiomatic in contemporary art, film and video. And yet, in certain quarters in the art

establishment these are two forms that still elicit controversy. You only have

to go to this as recently as the 2014 Turner Prize, which was awarded to the

Irish-born artist Duncan Campbell for his work It for Others, to appreciate how the essay audio-visual form (in

its various multiplying generic expressions) still creates aesthetic and

cultural static. This is incredible given how its lineage can be clearly traced

back to the historical avant-garde, film modernism, documentary cinema,

photojournalism, radio, and as we know, if we are tracing its arc back to its

literary essay origins back then we need to go the seminal French author and

traveller Michel Montaigne and even before him.

But

what I intend to do in this article is to speculatively discuss a recent

example of the form by the bold imaginative Australian independent filmmaker

John Hughes, whose exemplary oeuvre stands out in contemporary Australian

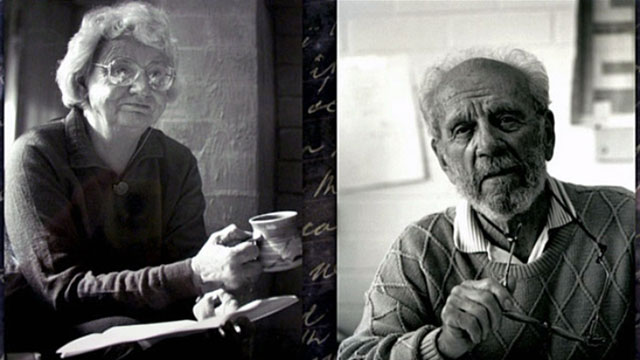

documentary film-making. I am referring to his little known, extraordinarily

crafted and compelling archive film essay about the not so well-known love

affair between two of this country’s major creative and public intellectuals,

the poet and activist Judith Wright and the cultural policy mandarin and

economist “Nugget” Coombs, aptly titled Love

& Fury (2013).

Their

clandestine love for each other lasted over 25 years and it symbolically

represents in many complex ways and nuances the intricate ethical, creative,

historical, and political vicissitudes of how our past literary, civic and

public life are elaborately intertwined shaping our post-colonial global and

national horizons. And also, as in the case of Wright and Coombs, the shared

adventure of letting go of one’s cultural cringe yoke in creating a republic on

‘our fatal shores’. (Robert Hughes).

What

we see and hear, time and again, in this poignant and resonant television

documentary, which was shown on ABC television quiet awhile back, through their

mutual love for this country and its first people, which stamps every archival

frame of this indispensable film, is their courageous, profound and poetic

understanding of what it means to accept and value our country and its first

descendants in our emerging turbulent world of neoliberal late capitalism,

(post) colonialism and climate change. Make no mistake about it: both Wright and

Coombs were fiercely dedicated and lyrical eco-warriors foreshadowing our

present day Anthropocene era.

In many significant ways, the underlying existential

and political theme of Hughes’ film critiques our public and private lives,

both in the past and in the present. It

is a devastating examination of how conservative, repressive and ‘life-dimming’

(Manning Clark) our past history has been. And if Wright and Coombs were alive

today they would be, one would imagine, vocal critics of Tony Abbott’s past and Malcolm Turnbull’s

recent ruinous political stewardship of this country. Our asylum seekers policy

of the last 20 years or so, clearly reeks of stubborn draconian cruelty, and

the ever-lingering remnants of our past “White Australia” policy would be an

anathema to our two subjects. Also, it pays us to remember that this film was

seen on the ABC, our unique national broadcaster, whose future now appears unfortunately

threatened by the encircling jackals of rampant free-market ideology. Including,

of course, judging by our recent Federal Budget, a certain group of right-wing

ideologues of the Coalition Government and the dreaded Pauline Hanson (One

Nation Party).

Raymond Gaita, in a timely and perceptive essay on

Simone Weil, the French philosopher and her posthumously published tract The Need for Roots (1949 [1952 in

English]), and our appalling government’s policy on asylum seekers, makes the forceful

point that we as artists and citizens need to re-examine the heroic and

grandeur character and limits of such concepts as dignity and human rights in

order to ethically hear the silent cry of the afflicted globalized asylum seekers

and the dispossessed. (1) Furthermore, Gaita deploys Weil’s sharply nuanced

ideas of being rooted in one’s national culture as a basic form of existential

and spiritual nourishment and country as ‘a vital medium.’ (2) Two vital

concepts that have importantly coloured the shared beliefs and actions of

Wright and Coombs in their tireless polemical endeavours to leave this world a

better place to live in.

In

fact, Hughes’ film reminds the viewer that all of us, living in this globalised

world of ours, are obliged to ensure that our ethical, cultural and theoretical

ideas and perspectives on ourselves and our institutions, values and priorities

at this historical juncture, more than ever before, are tested through our

individual and collective dangerously expanding carbon footprint on earth. In

other words, our geological imagination and understanding of how late

capitalism, climate change, power, space, time and technology are so

intricately braided with each other by the day are so compellingly urgent to acknowledge.

Before

we turn our attention to Hughes’s documentary in some detail, it would be

appropriate at this stage, to speak a little about Hughes’ own biographical

context, as one of our more imaginative, experimental documentary filmmakers

whose own aesthetic, artistic, cultural and historical roots and traditions as

an independent film-maker is primarily Australian in orientation, relating to

art, cultural politics and history.

His

prolific oeuvre, over the years, as a writer-director, include documentaries

dealing with various aspects of Australian race relations, film, history and

indigenous rights such as After Mabo (1997), River of Dreams (2000), and

“micro docs” such as Howard’s History (2004) and Howard’s Blemish (2004),

amongst many other sponsored and independent films. There are films dealing with the

Australian labor movement such as Film-Work (1981) and the widely-acclaimed hybrid work Traps (1986), amongst many others. Other films later are concerned with the early

Cold War including the already cited Film-Work and The Archive Project (2006), and Indonesia Calling: Joris Ivens in Australia (2009).

Between

1998 and 2008 Hughes collaborated with Betty Churcher to produce a marvellous

series of popular arts television programs including “micro docs” like Hidden Treasures (Film Australia/ABC TV

Arts, 2007) and in the following year An

Unstoppable Force: John Olsen with Betty Churcher (Film Australia/ABC TV

Arts, 2008).

Hughes

has also made a number of other acclaimed major films, installations/video art

and Super-8 films during the last 30 years that include a cinema feature What I Have Written (1996), All

That Is Solid (1988), One Way Street:

Fragments for Walter Benjamin (1992), and installations like November Eleven (1979), Works in Progress (1981), On Sacred Land (1984) and The Archive Project, ACMI version (2006).

The relationship and correspondence of Wright and Coombs

became, over the years, quite complex

and urgent in their shared demanding trajectory to engage in environmental,

indigenous and cultural issues salient to their common vision of Australia

shedding her colonial monarchist ties to England. However, Wright believed that their activist

activities were too profoundly important to be negated by the surrounding

negative political forces and consequently Wright became more guarded and

self-censorious about their relationship and correspondence. Indeed, Wright

with her increasing sense of isolation and loss of hearing, etc., burned a fair

amount of the early letters between them. Much to Coombs’ consternation.

1.

See Raymond Gaita, “Obligation

to Need”, in Thomas Keneally, Rosie Scott and Kathyrn Heyman (eds) A Country Too Far, Sydney: Penguin

Books, pp 288. back

2.

Gaita , Ibid. back

3.

Tom Griffiths, “The Art of Time Travel,” Melbourne, Black Inc., 2016. back

4.

See Griffiths, p.94. back

|

Published May 23, 2018. © John Conomos, May 2018

|